Sir

Morien: Black Knight of King Arthur’s Round Table

Few

documents portray the ethnicity of the Moors in medieval Europe with more

passion, boldness and clarity than Morien. Morien is a metrical romance

rendered into English prose from the medieval Dutch version of the Lancelot.

Morien

is the adventure of a splendidly heroic Moorish knight (possibly a Christian

convert), supposed to have lived during the days of King Arthur and the Knights

of the Round Table. Morien is described as follows:

“He

was all black, even as I tell ye: his head, his body, and his hands were all

black, saving only his teeth. His shield and his armour were even those of a

Moor, and black as a raven.”

Initially

in the adventure, Morien is simply called “the Moor.” He first challenges, then

battles, and finally wins the unqualified respect admiration of Sir Lancelot.

In addition, Morien is extremely forthright and articulate. Sir Gawain, whose

life was saved on the battlefield by Sir Morien, is stated to have “harkened,

and smiled at the black knight’s speech.” It is noted that Morien was as “black

as pitch; that was the fashion of his land — Moors are black as burnt brands.

But in all that men would praise in a knight was he fair, after his kind. Though

he were black, what was he the worse?” And again: “his teeth were white as

chalk, otherwise was he altogether black.”

“Morien,

who was black of face and limb” was a great warrior, and it is said that: “His

blows were so mighty; did a spear fly towards him, to harm him, it troubled him

no whit, but he smote it in twain as if it were a reed; naught might endure

before him. Ultimately, and ironically, Morien came to personify all of the

finest virtues of the knights of medieval Europe.

“It

should be noted that for a very long period the Dutch language used Moor and

Moriaan for Black Africans.”

Among

the Lorma community in modern Liberia, the name Moryan is still prominent.

MOORISH

NOBLES IN SPAIN. FROM THE CHESSBOOK OF ALPHONSO X

The

Expulsion From Spain and the Dispersal of the Moors

In

Iberia, Christian pressures on the Moors grew irresistible. Finally, in 1492,

Granada, the last important Muslim stronghold in al-Andalus, was taken by the

soldiers of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, and the Moors were expelled from

Spain. In 1496, to appease Isabella, King Manuel of Portugal announced a royal

decree banishing the Moors from that portion of the peninsula. The Spanish king

Philip III expelled the remaining Moors by a special decree issued in 1609.

Fully 3,500,000 Moors, or Moriscos, as their descendants were called, left

Spain between 1492 and 1610.

An

estimated million Moors settled in France. Others moved into Holland. A very

curious story in the Netherlands is that of Zwarte Piet (Black Peter). By some

accounts Zwarte Piet, the companion to Sinterklaas (Santa Claus), was a Moorish

orphan boy whom Sinterklaas adopted and trained as his assistant.

By

1507, there were numerous Moors at the court of King James IV of Scotland. One

of them was called Helenor in the Court Accounts, possibly Ellen More. There

were at least two other Black women of the royal court who held positions of

some status, and they are stated as having had maidservants dress them in

expensive gowns.

In

1596, Queen Elizabeth, highly distressed at the growing Moorish presence in

England, wrote to the lord mayors of the major cities that:

“There

are of late divers blakamores brought into this realm, of which kinde of people

there are already too manie.”

*Runoko

Rashidi is based in Los Angeles and Paris. He is the author of “Black Star: The

African Presence in Early Europe.” In August 2014, he is leading a tour group

through several cities in Western Europe focusing on the African heritage,

especially in the museum collections. For more information and to join the tour

write to: Runoko@yahoo.com or go to www.travelwithrunoko.com

The

Black Saint Maurice: Knight of the Holy Lance

Of

all the many Black men in the history of Europe, few have excited the

imagination more than Saint Maurice. He was a Black saint in an area then and

now that has very few Black inhabitants. He was also a Black knight. Indeed, we

could call him a knight in shining armor. He is no less than remarkable.

The

name Maurice is derived from Latin and means “like a Moor.” The Black Saint

Maurice (the Knight of the Holy Lance) is regarded as the great patron saint of

the Holy Roman Germanic Empire. He is also known, especially in Germany, as

Saint Mauritius. The earliest version of the Maurice story and the account upon

which all later versions are based, is found in the writings of Bishop Euchenus

of Lyons, who lived more than 1500 years ago. According to Eucherius, Saint

Maurice was a high official in the Thebaid region of Southern Egypt — a very

early center of Christianity.

Specifically,

Maurice was the commander of a Roman legion of Christian soldiers stationed in

Africa. By the decree of Roman emperor Maximian, his contingent of 6,600 men

was dispatched to Gaul and ordered to suppress a Christian uprising there.

Maurice disobeyed the order. Subsequently, he and almost all of his troops were

martyred when they chose to die rather than persecute Christians, renounce

their faith and sacrifice to the gods of the Romans. The execution of the

Theban Legion occurred in Switzerland near Aganaum (which later became Saint

Maurice-en-Valais) on Sept. 22, either in the year 280 or 300.

In

the second half of the fourth century, the worship of St. Maurice spread over a

broad area in Switzerland, northern Italy, Burgundy, and along the Rhine. The

major cities of Tours, Angers, Lyons, Chalon-sur-Saone, and Dijon had churches

dedicated to St. Maurice.

By

the epoch of Islamic Spain, the stature of St. Maurice had reached immense

proportions. Charlemagne, the grandson of Charles Martel and the most

distinguished representative of the Carolingian dynasty, attributed to St.

Maurice the virtues of the perfect Christian warrior. In token of victory,

Charlemagne had the Lance of St. Maurice (a replica of the holy lance reputed

to have pierced the side of Christ) carried before the Frankish army. Like the

general populace, which strongly relied on St. Maurice for intercession, the

Carolingian dynasty prayed to this military saint for the strength to resist

and overcome attacks by enemy forces.

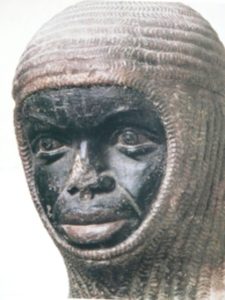

ST

MAURICE IN MADGEBURG

In

962, Otto I chose Maurice as the title patron of the archbishopric of

Magdeburg, Germany. By 1000 C.E. the worship of Maurice was only rivaled by St.

George and St. Michael. After the second half of the 12th century, the emperors

were appointed by the pope in front of the altar of St. Maurice, in St. Peter’s

Cathedral in Rome.

In

Halle, Germany, a monastery with a school attached to it was founded and

dedicated to St. Maurice in 1184. In 1240, a splendid Africoid statue of St.

Maurice was placed in the majestic cathedral of Magdeburg — the first Gothic

cathedral built on German soil. I was actually able to visit this cathedral and

photograph the statue in 2010. The facial characteristics of the statue are

described by historian Gude Suckale-Redlefsen in his classic work, The Black

Saint Maurice, as follows:

“The

relatively small opening in the closely fitting mail coif was sufficient for

the Magdeburg sculptor to produce a convincing characterization of St. Maurice

as an African. The facial proportions show typical alterations in comparison

with European physiognomy. The broad, rounded contours of the nose are

recognizable although the tip has been broken off.

“The

African features are emphasized by the surviving remains of the old polychrome.

The skin is colored bluish black, the lips are red, and the dark pupils stand

out clearly against the white of the eyeballs. The golden chain mail of the

coif serves, in turn, to form a sharp contrast with the dark face.”

A

center of extreme devotion to St. Maurice was developed in the Baltic states,

where merchants in Tallin and Riga adopted his iconography. The House of the

Black Heads of Riga, for instance, possessed a polychromed wooden statuette of

St. Maurice. Their seal bore the distinct image of a Moor’s head.

In

1479, Ernest built several castles, one of which he named after St. Maurice —

the Moritzburg. Under a banner emblazoned with the image of a Black St.

Maurice, the political and religious leaders of the Holy Roman Empire battled

the Slavs. The cult of St. Maurice reached its most lavish heights under

Cardinal Albert of Brandenburg (1490-1545), who established a pilgrimage at Halle

in honor of the Black saint.

From

the early 16th century, and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, hangs a

magnificent painting by Lucas Granach, the elder of St. Maurice, resplendent as

a knight in shining armor. In the Alta Pinakothek in Munich hangs the painting

by Matthias Grunewald of St. Maurice and St. Erasmus in heaven. Grunewald was

the greatest painter of the German Renaissance. And in the Gemaldegalerie in

Berlin is the painting by Hans Baldung Grien of St. Maurice under the banner

flag of the German imperial eagle on one side, a painting of the adoration of

the magi (with a Black king, the youngest of the three magi), in the center,

and St. George and the dragon on the opposite side. I have seen and

photographed all four of these magnificent art objects.

Between

1523 and 1540, people from throughout the empire journeyed to Halle to worship

the relics of St. Maurice. The existence of nearly 300 major images of the

Black St. Maurice have been catalogued, and even today the veneration of St.

Maurice remains alive in numerous cathedrals in eastern Germany.

No comments:

Post a Comment